Deus Ex Machina or An Evolution of Theater

In the age of metaverses transitioning from virtual realms to tangible spaces, Act 2 of our series “Immersive Realities: Art of the 21st Century?”, this article, ‘Deus Ex Machina or An Evolution of Theater,’ explores the fusion of real and digital landscapes, delving into the transformative evolution of theater and the immersive experiences that redefine the boundaries of human interaction and storytelling.

“Metaverses” no longer exist just “in your headset” – they are moving to spaces in real life, blending real space, digital space, and human interaction. Though, perhaps all of this does not need a fancy new term; it might just be the evolution of theater.

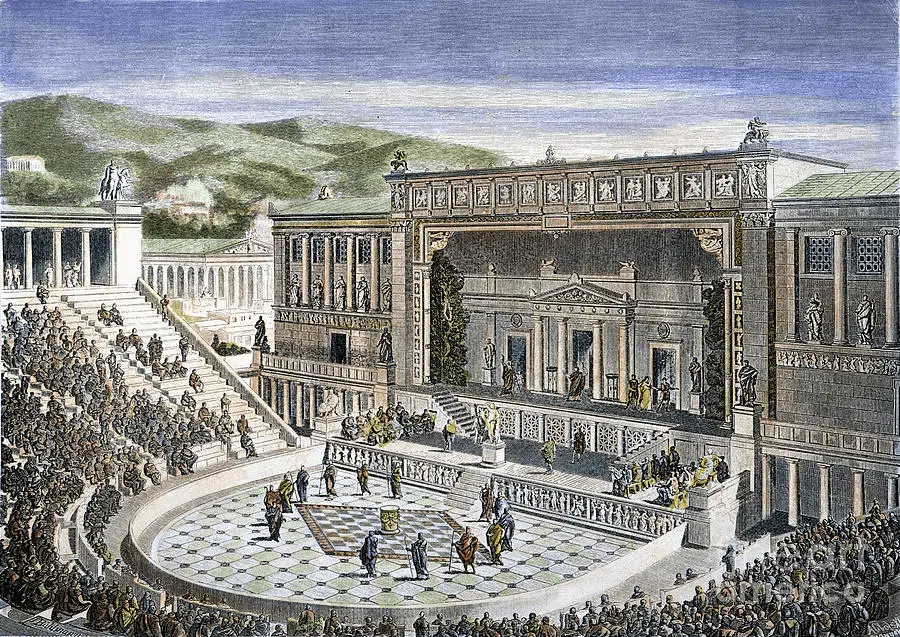

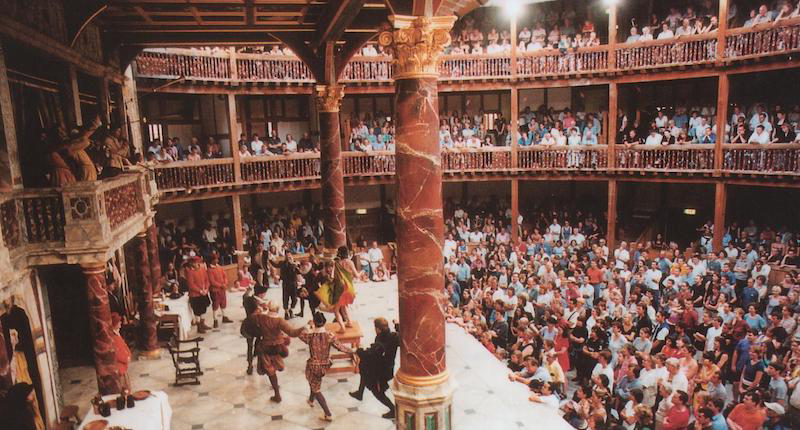

The Greeks invented the concept of theater as a place of public, civic discourse to reflect upon the inner reality of community; the myth was the storytelling of the Gods to reflect how humans were living in their own culture. The Greeks saw theater as the forum for community, and it was the place for civic discourse. In Shakespeare’s Time, the audience spoke to the play, cried out warnings to the characters, argued with the players, and built small revolutions against the plot. The theater was always meant to be interactive, immersive, and, to some degree, a manipulation of your reality in order to see a wider truth. This was when the audience lived in the “pit” and moved around it as though a participant.

Left: Greek Theatre – Right: Globe Theater

The concept of the “4th Wall” (when the actors pretend not to see the audience) is a relatively new technique. Developed in the 1800s when small box sets were created to make a scene “pop” – the three physical walls were manipulated as a way to play with time and space. The 4th wall was meant to “elevate” the play from the audience pit into serious art; it was meant to separate classes, as well as force the perspective of a play much like a painting.

Though, in the 1920s, the German writer, Bertolt Brecht broke the 4th wall when the actors looked directly at the audience, and spoke to them. His plays warned of a coming dictatorship, and the effect was so explosive it started both a cultural and creative revolution. Breaking the 4th wall is used in both theater and film, and demands a direct relationship between the character and the audience to include them, play with them, and ultimately, move them.

However, a technique used since the Greeks is the Deus Ex Machina (God as Machine) that was invented to be the voice of reason, or retribution, or, God(s). A large mechanical set (often with a person in it) would be lowered from the ceiling over the play and would speak directly to the characters in the play, and sometimes to the audience. Therefore, the use of the machine and the conversation with the audience has always existed – though Augmented Reality is a new addition. We turned to Redding for the trends in immersive theater as Deus Ex Machina:

“Immersive art involves the audience in a participatory experience, often in a narrative-driven environment such as that created by Sleep No More, a production that opened in New York City. I believe we’ve already crossed the tipping point into societal expectations of art being interactive and participatory, containing digital layers and elements. Digital natives like Gen Z and Alpha engage with traditional (non-interactive) art less and less, and museums have been incorporating immersive (AR/VR) elements in recent years — so we are fully into this new era.”

Sleep No More is a great example of theater embracing full immersion through AR – in this case, the production explores Shakespeare’s “Scottish Play”. Theater has often been the natural extension of new technology; ways for characters to fly, augmented video to move the plot, and inventive ways to trick our eyes. However, in the context of Sleep No More, the production works with the overlay effect of video and real characters and plants the audience into a movable feast throughout a hotel. So, there’s been a blending with new technology experiences and the emotional wildness of Shakespeare, and it’s a full-throated hit in New York.

The emergence of immersive theater experiences represents a captivating evolution in performing arts, yet it necessitates a consideration of potential counterarguments. A notable concern is the risk of overstimulation as immersive technologies become more prevalent, potentially overshadowing the subtlety and nuance inherent in traditional live theater. Critics caution against an excessive focus on visual and sensory stimuli, emphasizing the importance of narrative and character development in theatrical storytelling. Another counterargument centers on the potential dilution of the theatrical art form, with purists expressing concern that immersive technologies may compromise the essence of live, human interaction between actors and the audience, shifting towards a more technologically mediated experience. Ethical considerations also arise, particularly regarding user consent for data collection in immersive experiences. Transparency and clear consent mechanisms are crucial to inform audiences about how their data will be used, maintaining a balance between personalized experiences and privacy rights.

Additionally, the psychological impact on participants requires ethical scrutiny, as immersive experiences aiming to alter perceptions and induce strong emotions should be mindful of potential unintended consequences, such as emotional distress or disorientation. Now that we have provided the “warning” signs, let’s dig deeper into the exciting innovation that we discovered in theater utilizing Virtual Reality.

Kiira Benzing, VR Director, and founder of Double Life Studio believes that they are building a theater in the virtual space, and she believes the concerns about the negative psychological impact on audiences are unmerited. Benzing assured us that audiences have the experience to deepen their emotional memory through theater in VR. Her production, “Finding Pandora X” brought people into the small spaces of VR, though focused on the large feelings – and memories – that the mythological can bring to audiences, as participants. We asked her how she works with technologists, or not, to actualize the memory of those who become participants:

“We work very hard not just to create fun and interesting theater experiences but are trying to invoke a feeling and memory from people throughout that experience. So we are building in different interaction points throughout the story structure as a narrative so that the audience can participate, we are pulling at many modes of thought there – it is participatory storytelling, and we are using game mechanics to increase their sense of play. It’s not over the top, it depends on the show structure, but we are pushing the line between gamification and theatrical storytelling.”

The idea that the audience is no longer a passive observer only is where VR continues where Brecht left off. Benzing states, “When we shift the audience as a participant, now there is a bigger opportunity to break the 4th wall. I don’t know if Virtual Reality starts off as inherently breaking the 4th wall. I think it’s right on the edge! I do feel you have to design to break the 4th wall.”

Artists can now engage the audience about their desire to participate more. This, therefore, becomes both an artistic and technological choice for the artists to develop deeper experiences. In Pandora X, Benzing created a dialog with the audience as to how they might choose to engage with the production, and the audience chose to fly as their superpower. Through word cloud technology the audience chose to soar, so they built in an embodied form of flying where you are moving your arms, and you actively use your arms to fly. Her audience chose to fly around Mount Olympus, and the technology was defined by the audience’s request to engage directly with the narrative of the play.

This interaction with the audience as co-creator is extremely important to acknowledge. The interaction itself is reflective of the Greek model for theater: the audience is the participant, and the artists are in a direct relationship with them, and for them.

In 2023, The Sphere was launched in Las Vegas. Designed by Obscura Digital for Madison Square Gardens Company (upon its acquisition) this is a 360-degree projection sphere dome seating 1800 people. The dome has sound embedded into the walls to simulate our actual hearing, as well as smells to support the narrative. The band, U2 is its first live act, and auteur director, Darren Aronofsky has directed films about the planet to immerse the audience. Heralded as revolutionary, the dome is the confluence of art and technology, and simply as a theater space, it is both a playground for innovation and commercial success. Five years in the making, the $2.3 billion marvel stands 366 feet tall. The Sphere Entertainment Company said the arena’s opening brought in event-related revenues of $4.1 million, supplemented by $2.6 million from sponsorship and advertising.

The Sphere, Las Vegas

Though looking at The Sphere, it presents as the modern Deux Ex Machina. However, The Sphere does not need to be “lowered down” towards the stage – it is we who are lowered down into it. All the while as a piece of art, the dome is a living breathing object. And, though it is spectacular, it expands the question of what is real, and demands something even larger of us – where are you? For, simply put, the theater is meant to take you out of your second-to-second, moment-to-moment experience, and engage in a “willing suspension of disbelief” to help you see the world completely differently.

And, where audiences are responding to The Sphere with excitement, it is the scale of The Sphere that certainly matches the size of the Creative Economy and demands we take it seriously. We spoke with Alejandro Oropeza, CoFounder and Principal Design Strategy of Minds Over Matter Design, the primary architects of The Sphere. The team integrated their years on the frontline of digital immersion while studying historical innovations and methodologies of the theater, in order to best understand the relationship between the audience, the stage, and the theatrical elements/practices. He told us:

“Our work has firstly been about the development of Simulated Environments and understanding its use as an entertainment platform. Therefore human visual perception, technology innovation, and the interplay between virtual and real-world subject matter (IE Mixed reality (MR) or extended reality (XR) ), have always been primary factors and criteria in our work.”

Oropeza dug deeper to give us more context:

“In traditional theater, you have the front stage, framed by a proscenium, that engulfs a rear stage, with scenic layers that can be dropped down or shuffled in. All within a viewer’s front-facing perspective. The movie screen is simply a modern interpretation of this practice, utilizing only a small portion of our forward field of view. The IMAX theater increased this FOV but only marginally when you consider that our total field of view is 130 degrees vertical and 200 degrees horizontal. From the audience’s perspective, the classical amphitheater is actually a much wider field of view than our so-called modern theaters.”

Finally, how the move from live theater and how the audience perceives how live digital experiences impact our eyes, he concluded:

“In a true simulated environment, the human field of view should be boundless while keeping our peripheral vision intact. Also, the accuracy of how our eye’s stereo vision interprets depth and ultimately the vanishing point is paramount.”

So, is immersive theater art or entertainment? Is it overstimulation or the Greek’s dream of capturing the Gods – truly in the way we see things, now? Does it matter? What’s being tested is our desire for innovation to make us feel more deeply, and in an age of small screens and speed it takes something this large, this wild to permeate our ever-growing, thickening skins. The Gods of machines are being defined in this new age of theater, and a new age of immersion in a rapid state of creativity, and implementation. This is not a trend that’s coming; it has already arrived.

(Watch for Act 3 of this Article Series. Next up “The Challenge of Recognizing Arts Grandeur in Immersive Technology”)